Spiders are one of nature’s success stories, with spider webs distributed in nearly every corner of the world. Recently, the discoveries from the ca. 100 million year old Burmese amber of Myanmar shed important light on where spiders may have evolved from.

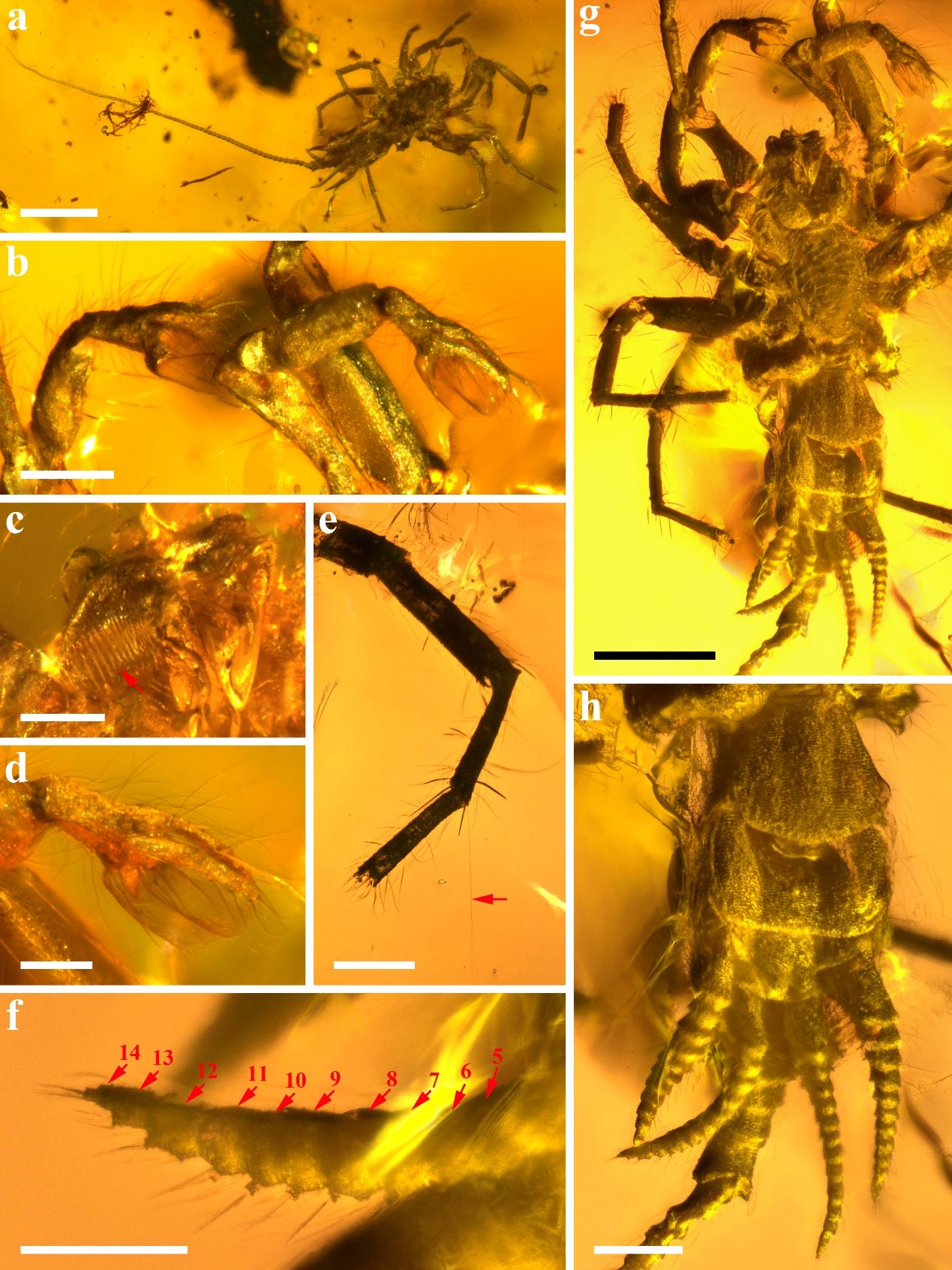

Photo of Chimerarachne yingi gen. et sp. nov. Image by WANG Bo

Chimerarachne is an extraordinary fossil spider from Burmese amber, described by an international research team led by Prof. WANG Bo from Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (NIGPAS), with the name comes from the way in which the new fossil seems to combine features of different arachnids, and is based on the chimera: a monster in Greek mythology composed of different animal parts.

These “Monster Spiders” are with tiny sizes, less than 2 mm long (excluding tail). The body can be divided into prosoma and abdomen, with six eyes are medially located near the anterior margin of the carapace. Their appendages are similar to those of modern spiders, including a pair of chelicerae, pedipalps, and 4 pairs of legs.

The fossils have four pairs of spinnerets, with anterior lateral and posterior lateral spinnerets bearing 14 and 12 articles respectively (each with silk gland). The most impressive feature is the long (at least twice the body length) and thin flagellum, which has more than 70 articles and bears numerous long setae. Such a long tail is similar to that of extant Uropygi (whip scorpions) and Palpigradi (micro whip scorpions).

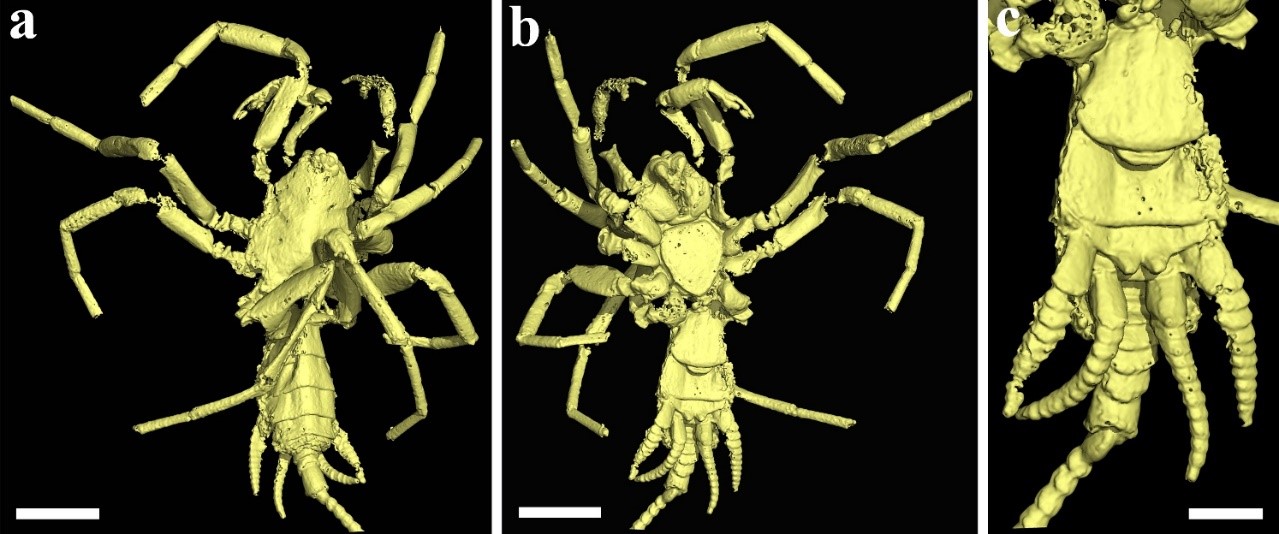

Micro-CT images of the monster spider Chimerarachne yingi from the mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. Image by HUANG Diying

The international team led by Prof. HUANG Diying from NIGPAS also studied these fossil spiders and suggested that the origin of Chimerarachne can be dated back to the ancient Devonian of New York, USA (359~419 million years ago), where fragments of Attercopus were discovered. They all have characteristic spider-like chelicerae and a long whip-scorpion-like tail (flagellum).

The researchers suggested that Chimerarachne is either the most primitive spider known, or else belongs to a group of extinct arachnids which were very close to spider origins. Either way, the implication is that there used to be a time when spiders still had tails.

Taken together, Chimerarachne has a unique body plan among the arachnids and raises important questions about what an early spider looked like, and how the spinnerets and pedipalp organ may have evolved.

These researches were recently published in Nature Ecology & Evolution titled by ‘Cretaceous arachnid Chimerarachne yingi gen. et sp. nov. illuminates spider origins’ and ‘Origin of spiders and their spinning organs illuminated by mid-Cretaceous amber fossils’.

Reconstruction of Chimerarachne yingi gen. et sp. nov. Image by YANG Dinghua

Reference:

1. Wang Bo*,Dunlop J.A., Selden P.A., Garwood R.J., Shear W.A ,Müller P., Lei Xiaojie, 2018. Cretaceous arachnidChimerarachne yingigen. et sp. nov. illuminates spider origins.Nature Ecology & Evolution. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0449-3.

2. Huang, Diying, Hormiga, G., Cai, Chenyang, Su, Yitong, Yin, Zongjun, Xia, Fangyuan, Giribet G., 2018. Origin of spiders and their spinning organs illuminated by mid-Cretaceous amber fossils.Nature Ecology & Evolution.doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0475-9.